DECONSTRUCTING PALAZZO VECCHIO: A Florentine Icon Reimagined

In 1299, construction began on what was then known as the Palace of the Priors (Palazzo dei Priori) under the direction of Arnolfo di Cambio (also architect of the new Cathedral). Then for over two centuries, it served as the seat of Florence's republican government.

In 1537, Cosimo I de'Medici (Duke, then Grand Duke) seized control of the Florentine state. In 1540, he expropriated its former headquarters as his official residence.

In 1565, Cosimo moved to the newly acquired Palazzo Pitti— leaving Arnolfo's structure with the name that it has born ever since: the "Old Palace" or "Palazzo Vecchio".

In 1737, the Medici regime came to an end. All of their palaces (including the old one) passed to the succeeding House of Lorraine until 1861, when Tuscany joined the rapidly unifying Kingdom of Italy.

From 1865 through 1871, during Florence's six years as interim capital, the Palazzo Vecchio housed the National Parliament.

In 1871, the royal court shifted to Rome and Arnolfo's monument became City Hall once again, reverting (more or less) to what it had been centuries before.

Locals call the Tower of Palazzo Vecchio "La Torre di Arnolfo" (Arnolfo di Cambio's Tower), expressing the distinctively Florentine urge to personalize cultural achievements and claim a family relationship with the inventor. Within a five-minute walk, we also have La Loggia di Orcagna, Il Campanile di Giotto and La Cupola di Brunelleschi.

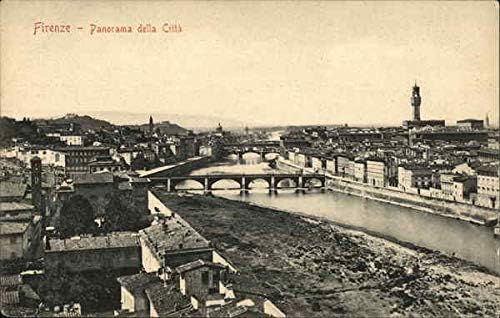

From time out of mind, this soaring structure has been the unchallenged symbol of Florentine identity —and of Florentine exceptionalism, many would say. Meanwhile, no other building embodies the city's history as completely as Palazzo Vecchio, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Arnolfo's Tower is nearly 100 meters high, so we catch glimpses of it wherever we go —in town or miles away, down along the river or up in the hills.

The history of taste and perception is a thing of its own, so I will focus only on two prints from a hundred years apart.

The delicately-hatched etching above is from the mid-1700s. It emphasizes the tower's noble height in isolation —almost too slender, it would seem, to remain standing century after century.

By the mid-1800s— the time of the stolidly descriptive engraving above— ponderous monumentality and picturesque elaboration had come to the fore.

In this strangely top-heavy rendering, the tower was evidently shortened to accomodate an oversized detailing of the superstructure.

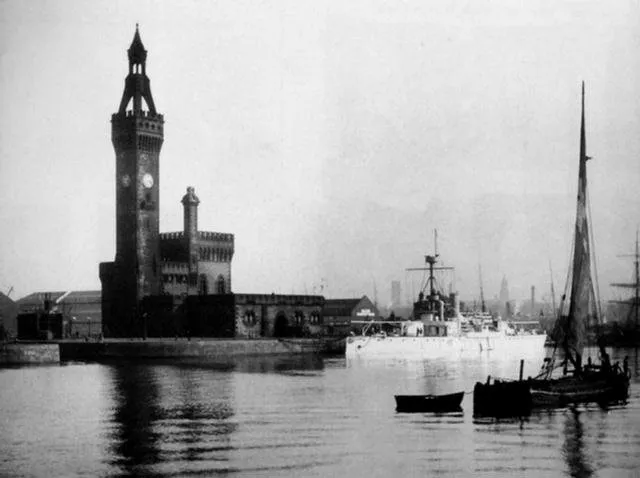

In 1863, a year after that second engraving, an eminently Victorian Torre di Arnolfo rose on the banks of the Mersey River, amidst the new port facilities in metropolitan Liverpool.

The architect Jesse Hartley set his lofty tower on the ground next to his Palazzo Vecchio surrogate —not above it, let alone projecting over the parapet, like Arnolfo's original. Hartley also placed a whimsical lantern on top.

Historical referencing aside, Hartley's tower represented a bold feat of hydraulic engineering. It generated water pressure to operate the bridges and locks.

The Central Hydraulic Tower lost its top-piece during the World War II bombing of the Liverpool Docks. The surviving port facilities were hastily repaired but ultimately abandoned in the 1990s.

Still eye-catching in its desolation, the Tower was recently proposed as the centerpiece of a state-of-the-art Maritime Knowledge Hub (which evidently stalled out in the planning stage).

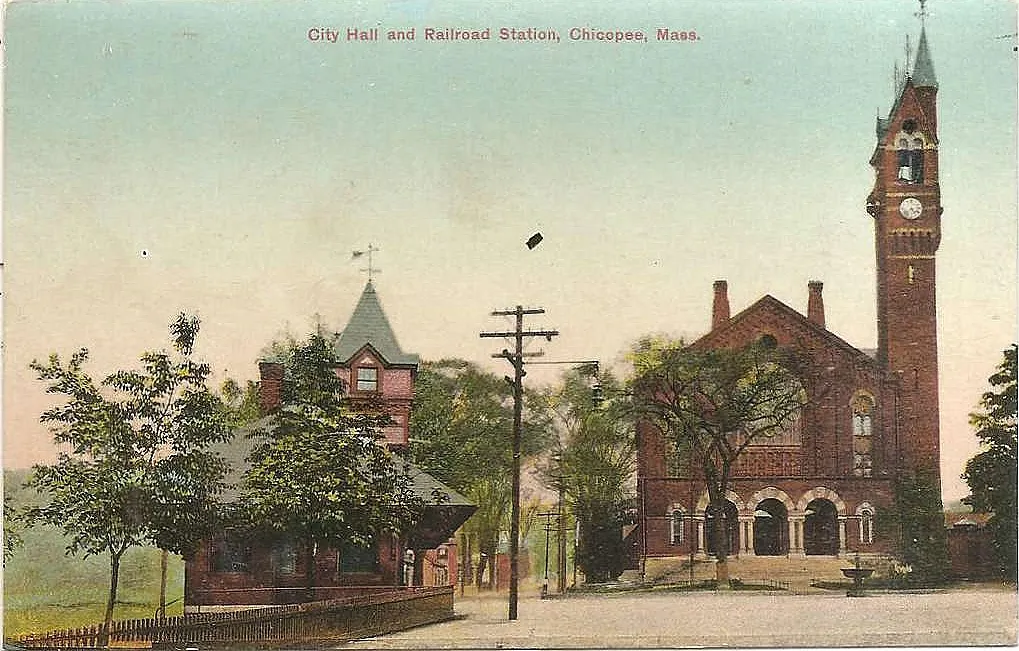

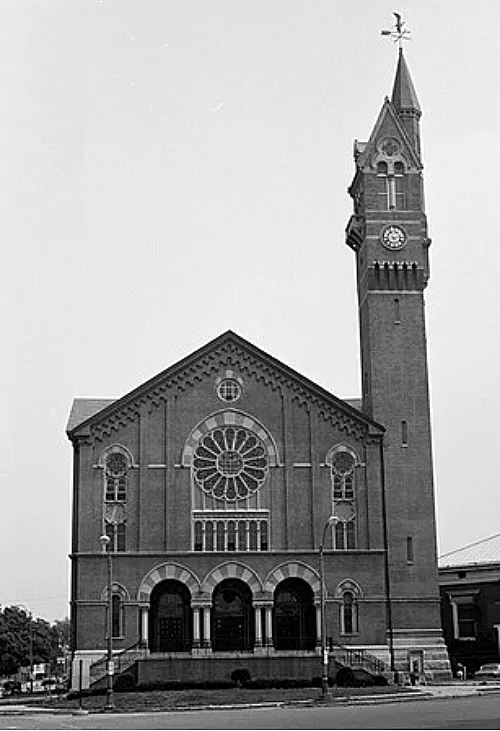

The next Torre di Arnolfo popped up in 1871, half a world away but still in the realm of Anglo-Romantic historical culture. This was in the smallish Massachusetts town of Chicopee.

The Boston Architect Charles Edward Parker designed an ambitious Town Hall with a Florentine Campanile attached. He placed it firmly on the ground next to the building (like its Birkenhead predecessor) and deposited a fanciful cap on top.

The Chicopee tower measures 45 meters, which the city proudly claims is the same height as the Florentine original. That is strictly true if you don't count Arnolfo's 50 meter head-start, springing from another very tall building.

Tower aside, the Chicopee structure has little to do with the Palazzo Vecchio (except that they are both town halls). In architectural terms, it channels a Northern Italian church, rose window included.

Apart from the Arnolfian tower, Bradford's Town Hall is sometimes described as "Venetian" in style for no apparent reason. The nearest I can come is "Romanesque Baronial with Tudor Collegiate Moments". In fact, the local architectural firm of Lockwood and Mawson submitted both a classical and a "Gothic" plan (to throw out yet another term) and the latter was selected.

Still, the Yorkshire model comes nearer than any of the others to reproducing the Florentine tower —in outline at least (the rest of the building is a whole other matter).

Lockwood and Mawson were perhaps unique in erecting the tower on top of the building (not alongside it). The battlemented top-piece is much as Arnolfo imagined (apart from the intricate gothic fenestration, the squaring of the rounded corner piers and the shift of the clock face to the lower parapet).

Today, the effect is probably even more startling than it was back in 1873, with the ancient Florentine tower poking out of a jumbled modernish setting.

"Why the Torre di Arnolfo?" We ask ourselves that question time and again when faced with latter-day approximations.

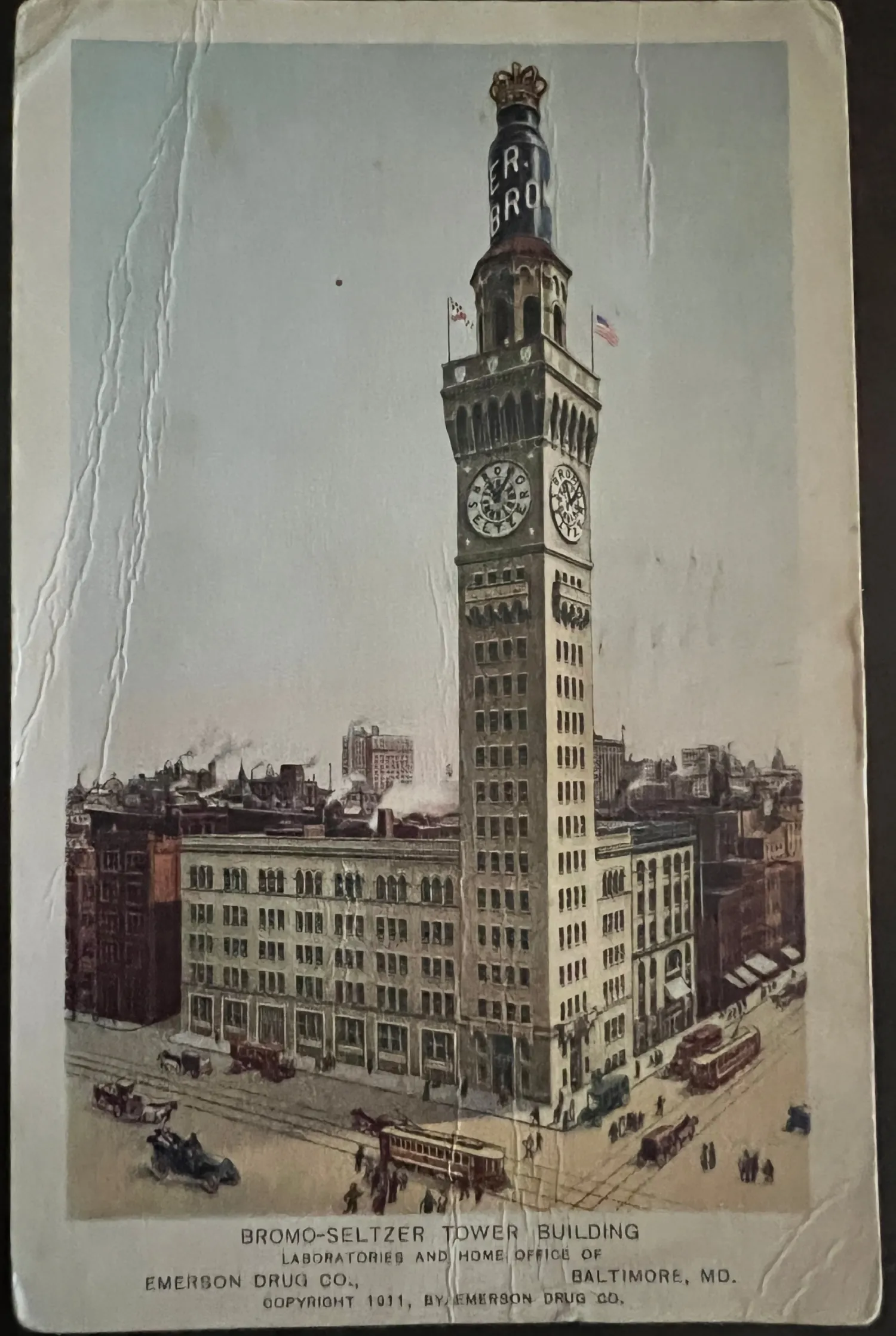

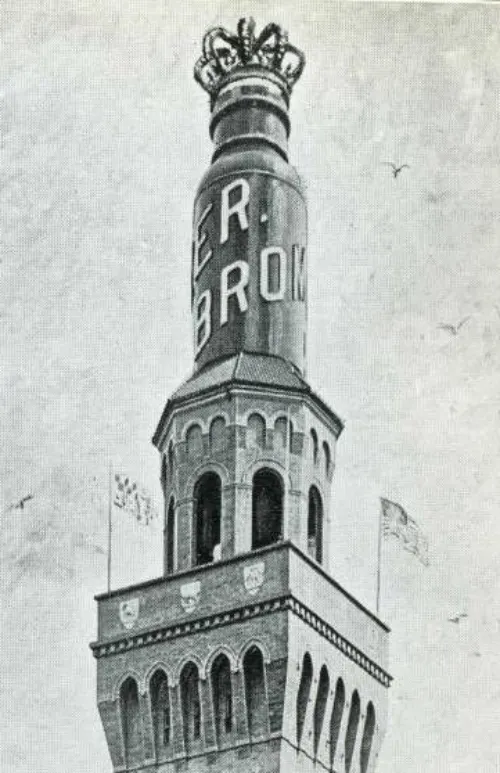

In the case of the Bromo Seltzer Building in Baltimore (realized 1907-11), we have a clear answer. In 1900, Isaac Edward Emerson, inventor of the wildly popular head-ache remedy, was visiting the Old Country with his Italian-American mistress. Their grand tour included Florence (of course) and the rest is history.

Emerson had a huge structure in mind, decidedly post-Victorian in style. It would include a state-of-the-art factory with corporate offices attached —in the 15-story Arnolfian tower.

Emerson used the distinguished local architect Joseph Evans Sperry and somewhere along the way, the genius of American merchandisng kicked in.

Atop the 88 meter tower (almost the cumulative height of Arnolfo's with Palazzo Vecchio included), they added a 16 meter Bromo Seltzer bottle (with crown). Intensely blue, internally illuminated and perpetually rotating, it was visible at night 20 miles away— helping guide ships to the port of Baltimore. (The Central Hydraulic Tower at Birkenhead had a lantern on top as well.)

Emerson died in 1931— perhaps a mercy, since Alka Seltzer was launched that very year, sending Bromo Seltzer into an irreversible decline.

The great bottle was removed in 1936. Cracks and other infirmities had begun to appear, not surprising since it was in constant motion. (For the record, the Birkenhead lantern lasted five years longer, until the Merseyside bombings of 1941.)

The redundant factory was razed in 1969 and replaced by a brutalist firehouse in cast cement— relieved only by the surviving tower (now an arts center, with studios and other facilities).

Last in the long list of things that Isaac Edward Emerson didn't live to see was the banning of Bromo Seltzer (and all bromides) in America in 1975. They were finally classified as poisons (which medical researchers had warned for years).

Time for an auto-biographical digession?

I grew up in a Maryland suburb, a bit nearer to Washington than Baltimore. So, the Bromo Seltzer Building was vaguely in my frame of reference.

Still, the Torre di Arnolfo that started me on the present quest is in Jerusalem and well off the Anglo-Victorian Axis.

I happened upon on it on one of my visits to Israel and was left wondering, since it appears on none of the lists that I have seen of Palazzo Vecchio derivatives (which include many with far lesser claims).

.webp)

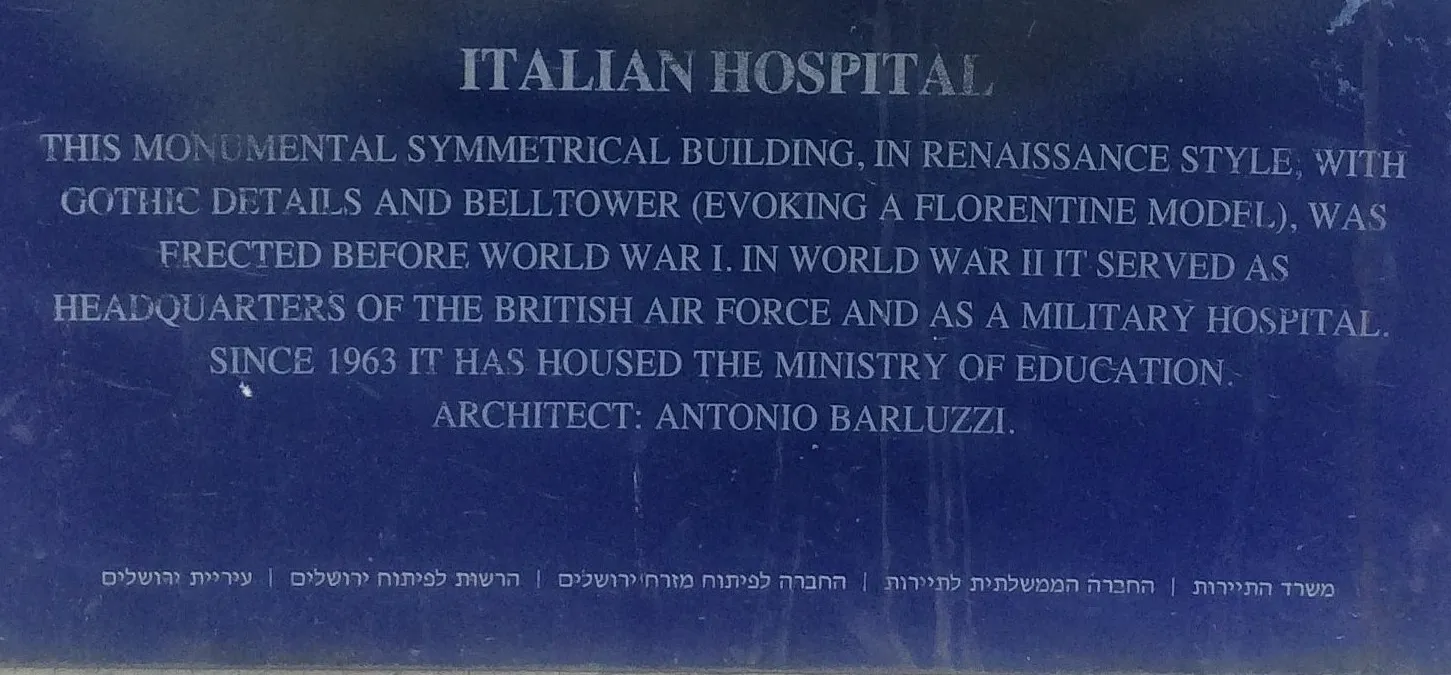

This tower, in fact, is even Italian —part of an imposing missionary hospital, realized in 1910-19, in a rapidly developing area west of the Old City.

The chief architect was Antonio Barluzzi (1884-1960), although his older brother Giulio was initially awarded the commission. It features a pair of matching Medieval city halls (housing hospital wards), anchored by a centrally planned Gothic church with a familiar bell tower attached. All in Jerualem stone...

.webp)

Antonio Barluzzi emerged from a family of committed Catholics, Vatican functionaries for generations. The Italian Hospital project set him up for life, since devout commission after devout commission then came his way— earning him the unofficial title of "Architect of the Holy Land".

Barluzzi also served from 1927 to 1937 as secretary of the Jerusalem chapter of the Italian Fascist Party (a fact that is largely ignored in the mostly gushing literature).

.webp)

Barluzzi thrills pilgrims with his vaunted ability "to translate Christian mysteries into art".

Meanwhile, he annoys the less susceptible (me included) with his aesthetic vapidity and general fussiness.

While clunky in its detailing, Barluzzi's first major work might have had a quasi-modern edge in its day.

This either aged well or didn't, depending on your point of view.

The "missionary hospital" lost its function in an emerging modern state with a national health system. In 1963, the complex was acquired by the Israeli Government and has been occupied by the Ministry of Education ever since.

Antonio Barluzzi's Torre di Arnolfo is seemingly the last in the series, coming a decade after the Bromo Seltzer Building in Baltimore. Still, it is hard to imagine that others don't remain to be found and I hope you will share your discoveries.

Barluzzi developed as an eclectic architect, in a country awash in historic buildings and more recent historicizing mash-ups.

Case in point: the campanile of Fiesole cathedral, easily visible from Florence just below and from the surrounding hills.

The effect of the tower is emphatically Arnolfian— which was clearly the intent— although it dates back to 1213, several decades before Arnolfo was born. The Palazzo Vecchio-style battlements were only added in 1739. The photo above was shot some 120 years later, just before a radical restoration of the Cathedral complex in 1878-85.

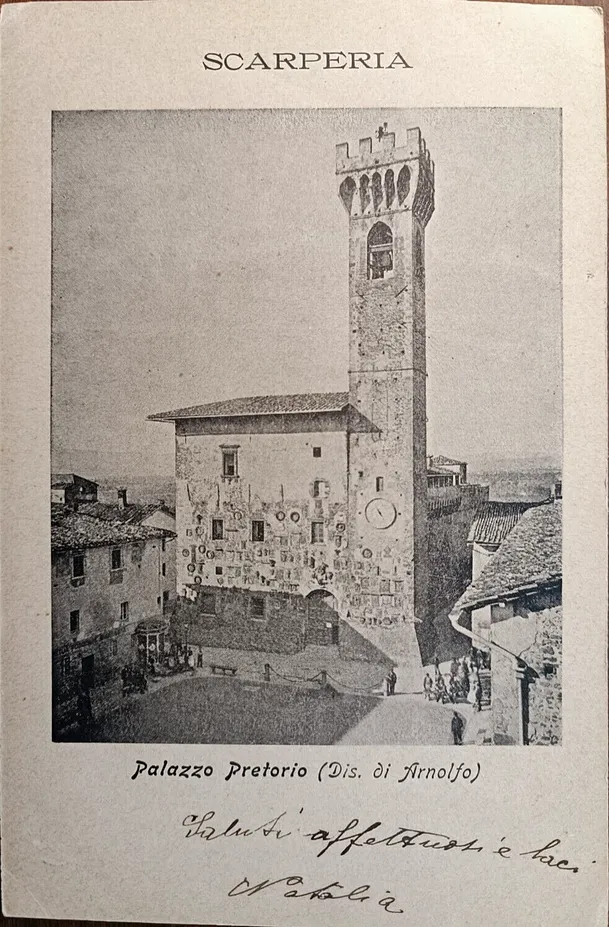

The Palazzo Pretorio (alternately Palazzo dei Vicari) in Scarperia, in the Mugello district northeast of Florence, is another case of Arnolfian backfilling— including an attribution to Arnolfo himself (who died four years before the Florentines founded Scarperia in 1306).

Its current appearance reflects ongoing reconstruction in that seismically unstable zone, especially after the earthquakes of 1542, 1611, 1919 and 1960.

The Florentine-style tower had its battlements by the 1560s— perhaps in the wake of the earthquake of 1542— when the painter Giorgio Vasari included them in an Allegory of Scarperia on the ceiling of the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio. (I rely on the testimony of experts who have gotten closer than I have.)

However, the Palazzo Pretorio didn't get the full treatment, main parapet and all, until after the 1919 earthquake.

The Palazzo dei Priori in Volterra (a substantial Tuscan town about 80 kilometers southwest of Florence) is probably the most thorough approximation of the Palazzo Vecchio, with its three levels of crenellation and tower rising from the body of the building.

Like various other civic palaces, Volterra's is older than Florence's (nearly a century older, begun in 1208). The emphatic battlements were apprently added only in the 16th Century, after the Medici annexed the town. The tower was rebuilt in its present form following an earthquake in 1846.

The recycling of Tuscan town halls in the Palazzo Vecchio mode is an intriguing topic but a complex one, best left for some other time.

The question becomes delightfully simple, however, when you take it abroad —to Britain, the United States or even Mandate Palestine.

The Arnolfian model (with or without Arnolfo) is always impressive and easily adaptable, whether you are planning a hospital, a hydraulic station or even another city hall.

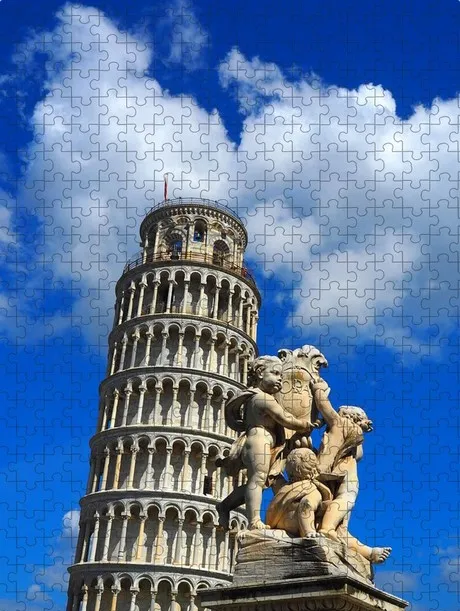

Sure, there is another even more famous Tuscan example —but it is dauntingly expensive to build, too fancy for general use and if it's not leaning, what's the point?

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.