CAESAR AUGUSTUS IN A CAGE: Mussolini's Museum of Roman Civilization

CONTENTS:

(1) CIVILITÀ

(2) THE AUGUSTUS THING

(3) IT'S ALL THERE...

(4) CAESAR WHO? (Part One)

(5) CAESAR WHO? (Part Two)

(6) "CAESAR WHO" UNCAGED

(1) CIVILITÀ

The word CIVILTÀ is essentially untranslatable. In English, it embraces everything from "civilization" to "culture" to "ethos" to "way of life", including government institutions, religious beliefs, social customs and the practicalities of daily existence.

Not to mention stuff and more stuff... Masses of what academics now call "material culture".

Entering the Museo della Civilità Romana in the EUR district of Rome.

Mussolini's museum offers an imposing blend of Roman grandeur and Egyptian permanence and it figured prominently in his plans for the (failed) 1942 World's Fair in Rome—marking the twentieth anniversary of the Fascist Revolution.

For Benito Mussolini, expansive vagueness was the key to the concept's beauty —like his other favorite shibboleth: ROMANITÀ (Romanness).

But due to the vicissitudes of war and the collapse of the Fascist Regime, the Museum did not open to the public until 1955—ten years after the Duce's death—proclaiming its curious message to a different Italy in a different world.

(2) THE AUGUSTUS THING

Mussolini expropriated Caesar Augustus as his historical alter ego.

That made perfect sense —if you delighted in the Duce's mythic style, without worrying too much about documented facts.

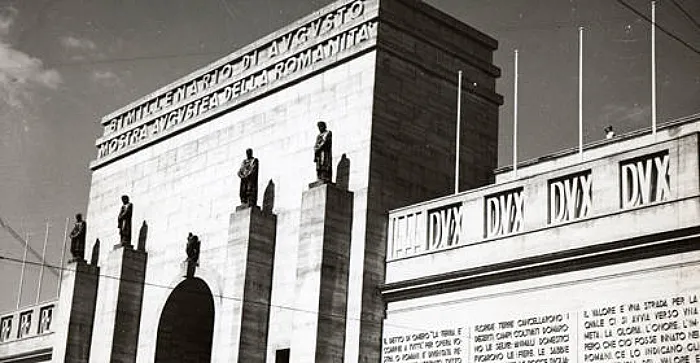

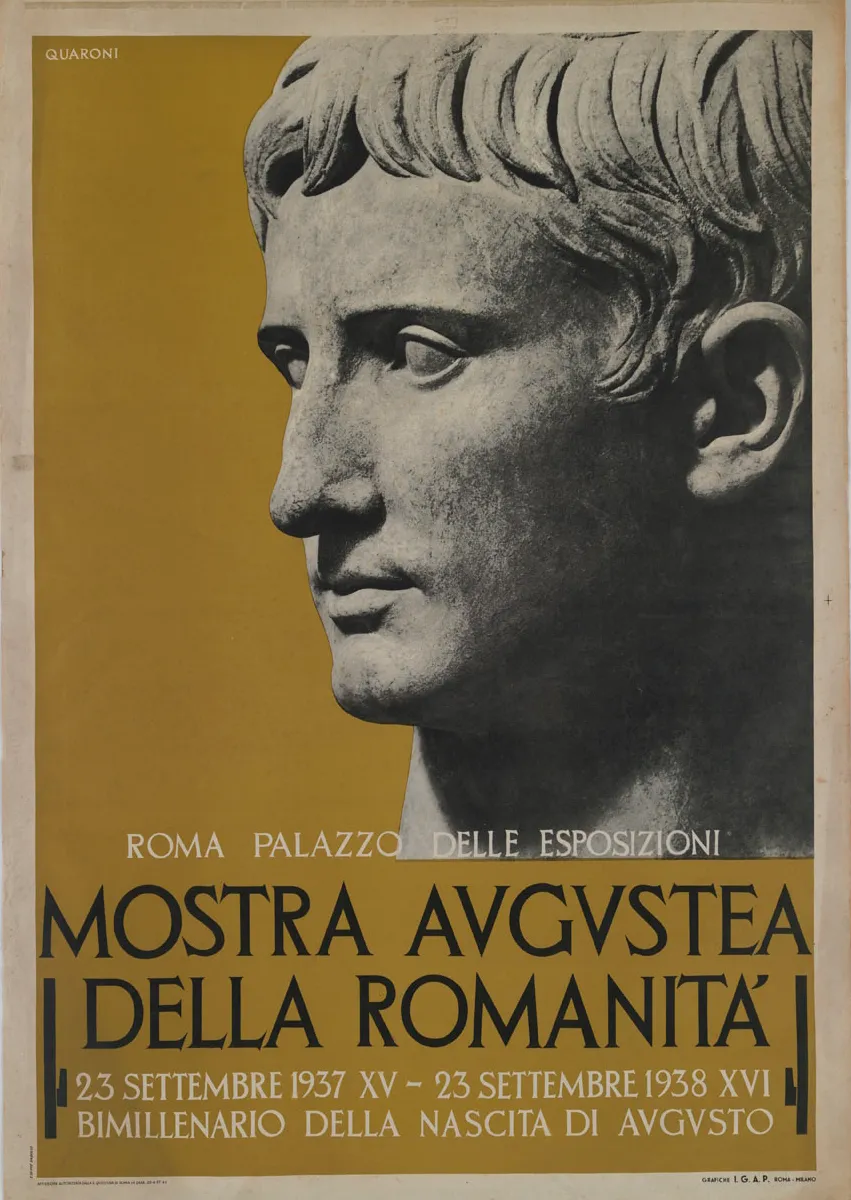

Then there was the 1937 Mostra Augustea della Romanità (Augustan Exhibition of Romanness), marking the (more or less) two-thousandth anniversary of Caesar Augustus' foundation of the Roman Empire.

The Augustan Exhibition of Romanness at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in the heart of the city was a public sensation.

After its closure in 1938, there was a groundswell of support for giving this material a permanent home.

In 1939, the FIAT organization under the direction of the all-powerful Gianni Agnelli took on the project —ordering a grand new museum in the emerging EUR district, designed to host the never-was 1942 World's Fair.

And today, the address of the Museo della Civilità Romana is: Piazza Giovanni Agnelli, 10.

FOR MORE ABOUT THE WORLD'S FAIR PROJECT:

E.42 (ROME)

(3) IT'S ALL THERE...

Back in the first centuries of the Common Era, when the real Roman Empire held sway, ROMANITAS (Romanness) might have had a concrete ideological meaning.

But what is it like today, visiting the Museo della Civilità Romana —now that Mussolini is long dead and Augustus merely one of the exhibits?

"Quaint" is a word that would have made the Duce wince. Political posturing aside, the institution's mandate was scientific —to compile all surviving evidence of Roman customs and practices. Including law, religion, technology, commerce, art, music and so on.

At its heart, the Museum is an immense walk-in encyclopedia—a thematic succession of fifty-nine vast rooms (most of the ceilings are over thirty feet high).

Each is filled with casts, copies, diagrams and reconstructions (but not original works), illustrating every conceivable aspect of Roman civiltà.

%2520enlarged.webp)

Seventy years ago, the museum was at the cutting edge of archeological scholarship.

Today, the place is still all-encompassing —rich and varied, intriguing and informative, evocative and inspiring ...and inescapably quaint.

The most celebrated exhibit—then and now—was a huge plaster model of ancient Rome (measuring some 700 square feet).

In 1933, it was commissioned by the fascist regime and figured prominently in the 1937 Augustan Exhibition of Romanness —although it replicates Rome in the Age of Constantine, some three centuries after Mussolini's favorite Caesar.

Like everything else in this museum, the great model was intensely researched and gravely serious in intent.

Still, it offers endless scope for escapist fantasy —for visitors in our day and presumably the Duce in his.

We can lose ourselves for hours, wandering through the miniaturized intricacies of the Eternal City —putting the pieces together as we go.

We see Ancient Rome through our own eyes but also through the eyes of the scholars and craftsmen who gave age-old memories tangible shape.

These days, computer programs can do all of this for us and more —in greater detail and with special effects too.

But we don't make the same effort, so we don't engage as intensely and the experience doesn't feel nearly as real.

.webp)

(4) CAESAR WHO? (Part One)

No one was paying much attention to this caged bronze figure, half in and half out of the museum, under a perpetual layer of dust.

Was he master of the house? Was he a presiding deity? Or was there simply no room inside?

"Augustus Caesar" automatically came to mind when I first wandered by many years ago.

That was an easy assumption, considering the distinctive Julio-Claudian hairstyle and the no less distinctive historical context— Mussolini's cult of the First Emperor.

Now I am rereading this old post (as it was on my previous website), looking at my old photos and having doubts.

Who am I seeing here ... really?

And who did people think they were seeing —back in the day— when the Museo della Civiltà Romana came into being?

In the 1930s, Mussolini ordered a host of such monumental bronze figures, mostly male and usually in armor.

Mussolini's love affair with big bronze emperors emerged from his excavation of the forum area in Rome.

In ideological terms, that was ground zero for his imperial program, so the Duce left no stone unturned— devastating a vast archeological site and a broad swathe of the city.

For Benito Mussolini, Julius Caesar was the beginning of the story— Dictator Perpetuus during his own lifetime, but not Imperator Caesar like his successors.

A year later, in 1933, the Duce shifted him to a more commanding position and he was joined by matching figures of Augustus, Trajan and Nerva, marking their respective forums.

Casts of Vespasian and Titus were also ordered but never realized.

In 1934, a bronze Hadrian was installed —all the way across town —in front of his imposing riverside tomb near the Vatican.

The Fonderia Laganà, a historic metal casting facility in Naples, cornered the market in government commissions of this kind, largely abandoning their previous specialization in smaller decorative works. As soon as this production was up and running, Mussolini launched an expansive program of Imperial outreach, dispatching bronze avatars throughout Italy and sometimes abroad.

For continuity of image, the Fascist regime selected a few antique prototypes and focused on these.

The designated Julius Caesar was a heroic marble statue, installed in the Aula Giulio Cesare in the Senatorial Palace on the Capitoline Hill only two years earlier in 1930.

In 1935, Mussolini sent a matching set of Julius and Augustus bronzes to Turin, to anchor a new Imperial park around the old Porta Palatina (the northern gate to the Roman city of Iulia Augusta Taurinorum).

As expected, the Capitoline Julius Caesar was the source for one work and the Augustus of the Prima Porta the other.

.webp)

Since 1933, a bronze Augustus of the Primaporta marked the starting point of the Via dell'Impero (Way of Empire), the newly-conceived processional route from Palazzo Venezia (the Duce's official headquarters) to the sea.

%2520enlarged%2520.webp)

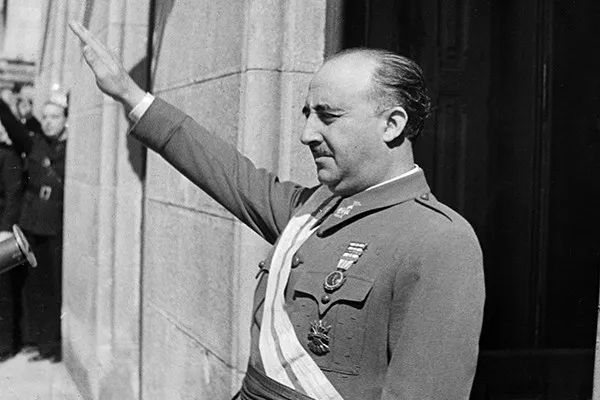

In 1941, the Duce sent off a standard order Augustus of the Prima Porta to Zaragoza, Spain.

This was evidently the last of its kind from the Fonderia Laganà and a curious coda to a long story.

By then, the Fascist Ventennio (1922-42) was sputtering to its end —but if the Duce's days were numbered, the Caudillo still had another three decades to run.

Fancifully or not, it is easy to imagine the beleagured Italian despot passing the mantle of neo-Empire to his Iberian fellow-traveler.

Not all of Mussolini's bronze heroes sprang from a single identifiable source—but for centuries, mix-and-match had been the name of the game for collectors, curators and restorers of antiquities.

Case in point: The Nerva in Mussolini's Forum Series is a pastiche that cannibalizes at least one other pastiche.

The armored torso comes from a made-up figure in Naples, now with a bearded head of Lucius Verus.

A detached head of Nerva in Rome is the apparent source for the new Forum likeness.

(5) CAESAR WHO? (Part Two)

If this statue wasn't meant to represent Caesar Augustus, it lands very near.

The facial type identifies him as an early member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (the first Imperial family, running from Julius Caesar through Augustus, Tiberias, Caligula, Claudius and Nero).

Then there is the forward-combed hair, which survives as a meme until the present day.

Looking back in history, however, the so-called "Caesar Haircut" seems to have vanished as an item of Imperial style after the death of Nero (last of the Julio-Claudians) in 68 AD—although several centuries of Caesars were yet to come.

The leading contenders are Augustus' grandsons Gaius and Lucius, both of whom launched distinguished military careers but died young without ascending the Imperial throne,.

%2520detail.webp)

%2520reduced.webp)

The breastplate —with its gorgon emblem and confronted griffins —dates from more or less the right period, but it needn't have been attached to this particular head.

In fact, the thunderbolt on the shoulder flap seems to suggest a deceased and probably deified emperor. Gaius and Lucius were neither emperors nor deified but Augustus was both.

There is an unmistakeable family resemblance between the Museo della Civiltà Romana bronze and Augustus Caesar. But back in the 1930s, when the work was presumably cast, did people actually think that it was Augustus himself?

In those days, less was known than now about the iconography of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, so it is easy to imagine a range of genuinely ancient items loosely identified as the first emperor.

It is less easy, however, to imagine the Fascist regime commissioning a large and expensive statue of Augustus (for whatever purpose) that was as far outside the parameters as this one.

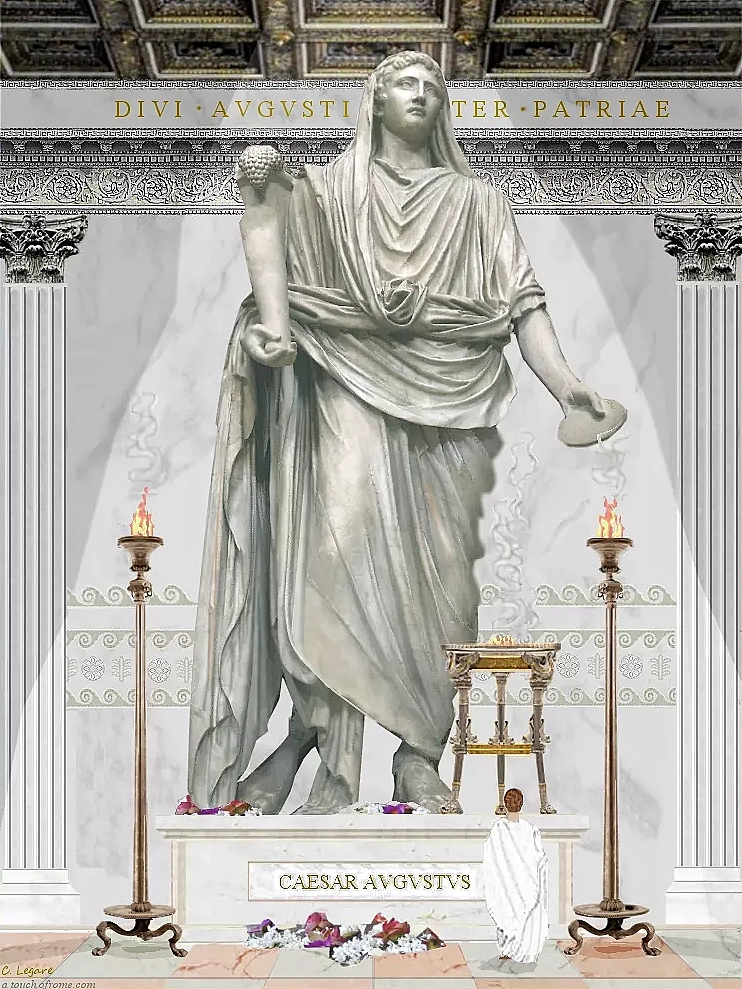

In Rome, whether Ancient or Fascist, Imperial prototyping was seldom casual. In the great hall of the Augustan Exhibition of Romanness, three canonical images encapsulated the ethos of the First Emperor.

To the left of the Inner Sanctum stood the iconic Augustus of the Primaporta —revealing him as a bold general, favored by the gods.

To the right was another relatively well-known representation of Augustus, showing him as Pontifex Maximus (High Priest).

In the middle, set off on its own, is the most intriguing exemplar of all. This much restored marble came to the Vatican Museums from a Neapolitan ducal collection.

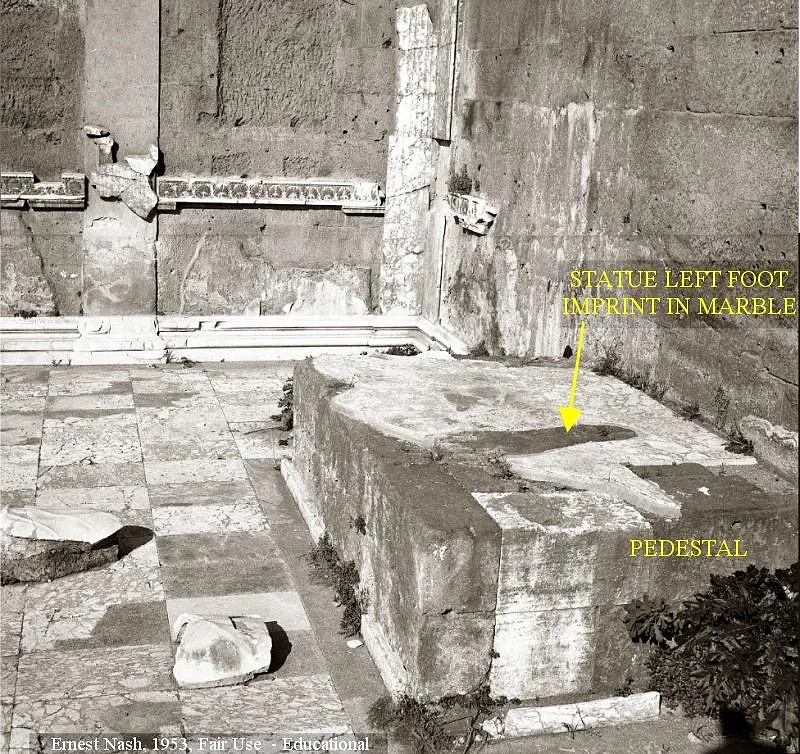

Known as the Genius (or Spirit) of Augustus, it reflects a colossal statue that still survives —just barely —in the precincts of his Forum.

This cultic figure, an estimated 11 meters in height, towered over Imperial devotees and casual sight-seers alike.

It's head, hands and feet were fine marble but the rest probably painted wood with iron supports.

This is the image of Augustus Caesar most properly associated with his Forum, if you are a stickler for historical accuracy which Benito Mussolini was not.

Always on mesage, he opted for the instantly recognizable Prima Porta type, when he decided to place a statue on that spot in 1933.

(6) "CAESAR WHO" UNCAGED

In the five years between the first and second photos (above), Caesar Who? was not cut entirely loose. He was, however, given a bigger cage.

Still, the old questions remain: Who is he anyway? And why is he lurking in that particular place?

The bronze cast that we are looking at is obviously old but not ancient, bearing a strong resemblance to Fonderia Laganà products of the Mussolini period.

Was it commissioned for the Museum or did it merely land up there? If so, when?

Is it a relic of the 1937 Augustus show? Or else, did it come from some other project —maybe one commemorating Augustus' descendants?

In any case, Caesar Who? emerges as a distinct oddity in the Museo della Civilità Romana —a monumental bronze (presumably destined for public display) in a collection of ingeniously colored plaster replicas of anything and everything (primarily didactic in scope).

Some or all of these questions could presumably be answered in the archive of the Museo della Civilità Romana, in files going back to the 1930s, '40s and '50s. Unfortunately, I don't see myself there on the spot, any time soon— diving into that intriguing material.

So, I did what scholars have traditionally done when they run into a wall. I threw myself on the mercy of the curator in charge —firing off an e-mail, outlining the little that I know and the great deal that I don't. Now I am awaiting a reply, so stay tuned...!!!

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.