Carnival Blood: Table of Contents and Chapter Summaries

%20mask%20detail%2001.webp)

●Acknowledgments

Why did I write this book? Where did this project take me? Who helped me along the way?

●List of Illustrations

Visual records of the Carnival Blood journey, includiing many original photographs.

●Chapter One: A Tale of Two Michelangelos

In the ancestral home of the Buonarroti family in Florence, I discover the lost manuscript of L’Ebreo (The Jew)—a rough draft of a rollicking entertainment in the style of the Commedia dell’Arte, written for the Carnival of 1614 at the Medici Court but never published nor performed.

The author was Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger, the leading Florentine playwright of his day—also the great-nephew, heir and namesake of the renowned painter, sculptor and architect.

One question leads to another... Why Florence? Why 1614? Why Carnival? Why Michelangelo the Younger? Why Jews? And then the most intriguing question of all: Why did this fresh and very funny play disappear from sight as soon as it was written?

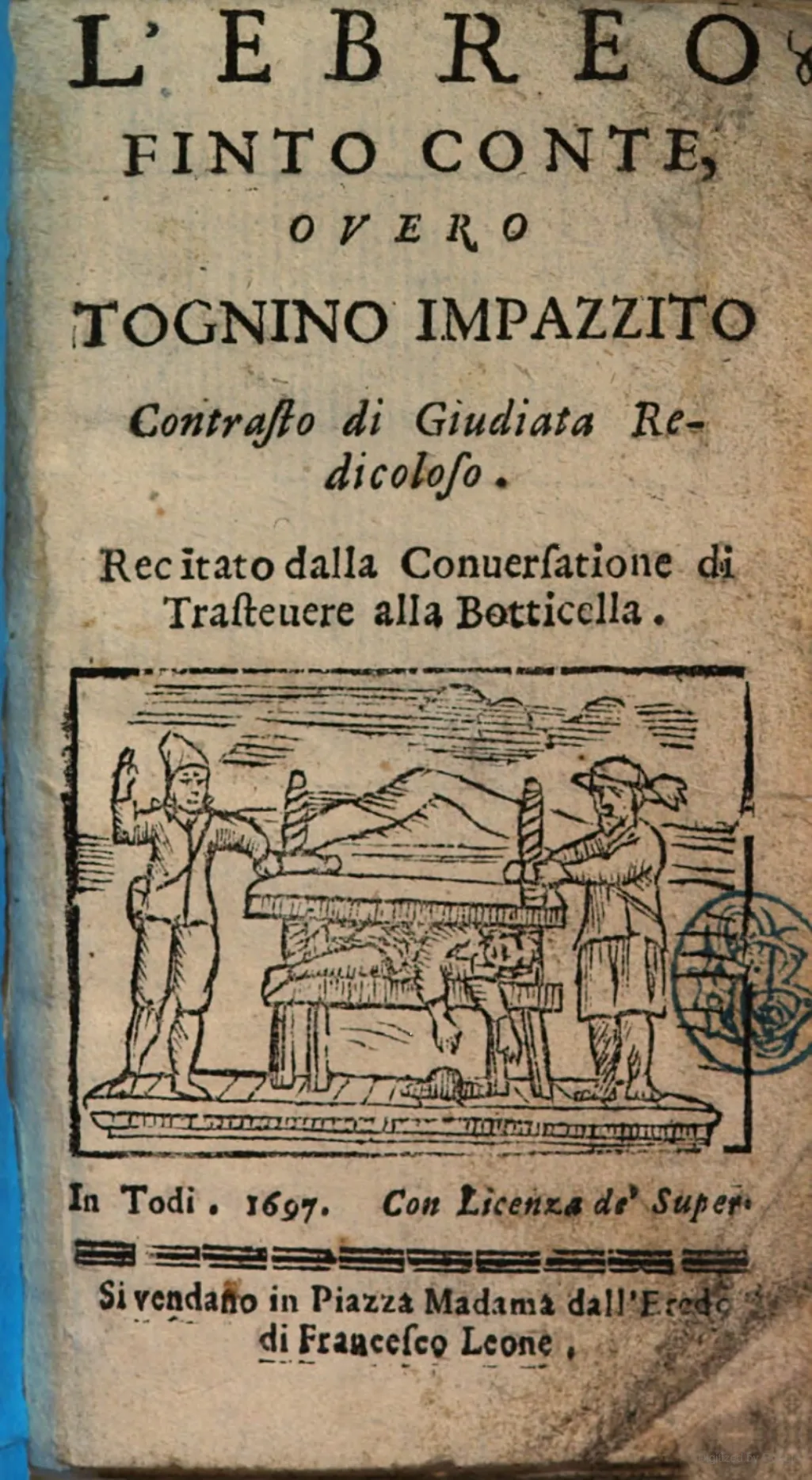

●Chapter Two: The World of the Jew Plays

The curtain goes up on an astonishing world of Jews—real and imagined, onstage and off. Centuries ago, “Jew Plays”—alternately humorous and blood-curdling—were an essential element of Italian life, especially during the Carnival season.

What did these boisterous entertainments say to audiences at that time? What is their enduring (if uncomfortable) message today? This chapter begins in Florence, then shifts to Rome, where these ancient “Jew Plays” still echo in surpising ways.

●Chapter Three: Blood Rites

Carnival was—and is—the annual festive season between Epiphany and Lent, filled with theatrical activity of every sort. For centuries, anti-Jewish bigotry was its animating force.

How do we explain the fatal relationship between Passover and Easter, Carnival and Lent, Jews and Carnival, and Jews and Blood? How do “Jew Plays”—Buonarroti’s and others—fit into this picture?

In search of an answer, I trace the dreadful history of the Blood Libel, the ancient conviction that Jews killed Christian children to obtain blood for their Passover matzohs.

In Italy, Trent 1475 was the most devastating Blood Libel of all. I follow its story—on the ground in Trent—from the not-so-remote past until the present day.

●Chapter Four: Jews as Jews

How does history—glorious, banal, horrifying and absurd—shape our daily lives today? Why is being a Jew in Italy still such a strange and often bizarrely comical experience?

As I delve into the realities of Buonarroti’s Jewish comedy, these questions loom larger and larger. I begin in Trent, in the long shadow of its notorious Blood Libel. Then I retrace my own journey through the present and the past, with many strange-but-true encounters along the way.

●Chapter Five: The Passion of Christ (Rome)

Rome is the “Eternal City”: ancient seat of empire, perennial cross-roads of cultures and one of the most overwhelming places on earth. For two thousand years, Rome has also been the capital of world Catholicism and the ultimate showcase for the Church’s relentless obsession with real and imagined Jews.

Again and again, during the long run from Epiphany through Carnival and Lent to Holy Week and Easter, Christians masqueraded in stereotypical Jewish” costumes, shouted derision at coerced foot-races by naked Jews, laughed at outrageous “Jew Plays” and were roused to homicidal fury by dramatic reenactments of their (alleged) killing of Christ.

Most notorious of all was the Passione di Cristo (Passion of Christ), written by Giuliano Dati around the year 1490, then regularly performed on Good Friday to deadly effect. In Rome today, the past is never just “the past”—as I discover again and again.

.webp)

●Chapter Six: The Passion of Christ (Sordevolo)

Giuliano Dati’s Passion of Christ was last staged in the Colosseum on April 4, 1539, fomenting violent anti-Jewish riots. It was then banned by the pope himself, for the sake of public order, but only in his capital city.

During the centuries that followed, Dati’s magnum opus was reprinted dozens of times throughout Italy. Today, it is still performed—in all its horror and on a monumental scale—in Sordevolo, a pleasant but otherwise unremarkable village in the foothills of the Alps.

To learn the true story of this startling survival, I needed to go to Sordevolo during the Passion season and watch this drama unfold.

●Chapter Seven: Jews Onstage, Jews Offstage, Jews Backstage

Why do we seldom hear about the Golden Age of Italian Jewish Theater, based in Mantua during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries?

Jewish actors, Jewish playwrights, Jewish musicians, Jewish singers, Jewish dancers, Jewish stage managers and Jewish impresarios won acclaim throughout Italy but are now seemingly forgotten. Leone de’ Sommi, Isacco Massarani, Simone Basilea, Salamone Rossi and Madama Europa were all stars in their time, with careers documented in historical archives.

Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger knew many of these Jewish protagonists by reputation and perhaps in person too. How did they influence his Carnival comedy, L’Ebreo (The Jew)? What is their legacy today?

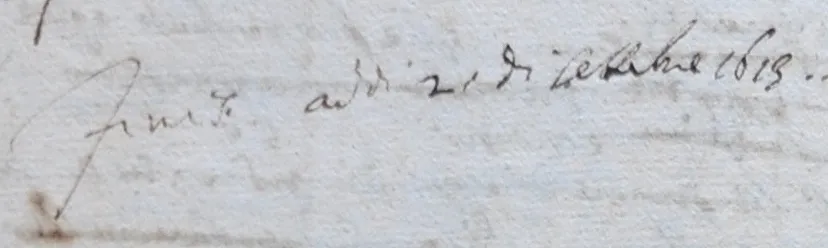

●Chapter Eight: September 21, 1613

“The Jew, a Comedy /Finished on the 21st day of September 1613." Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger inscribed this at the end of his own manuscript but what did he really mean?

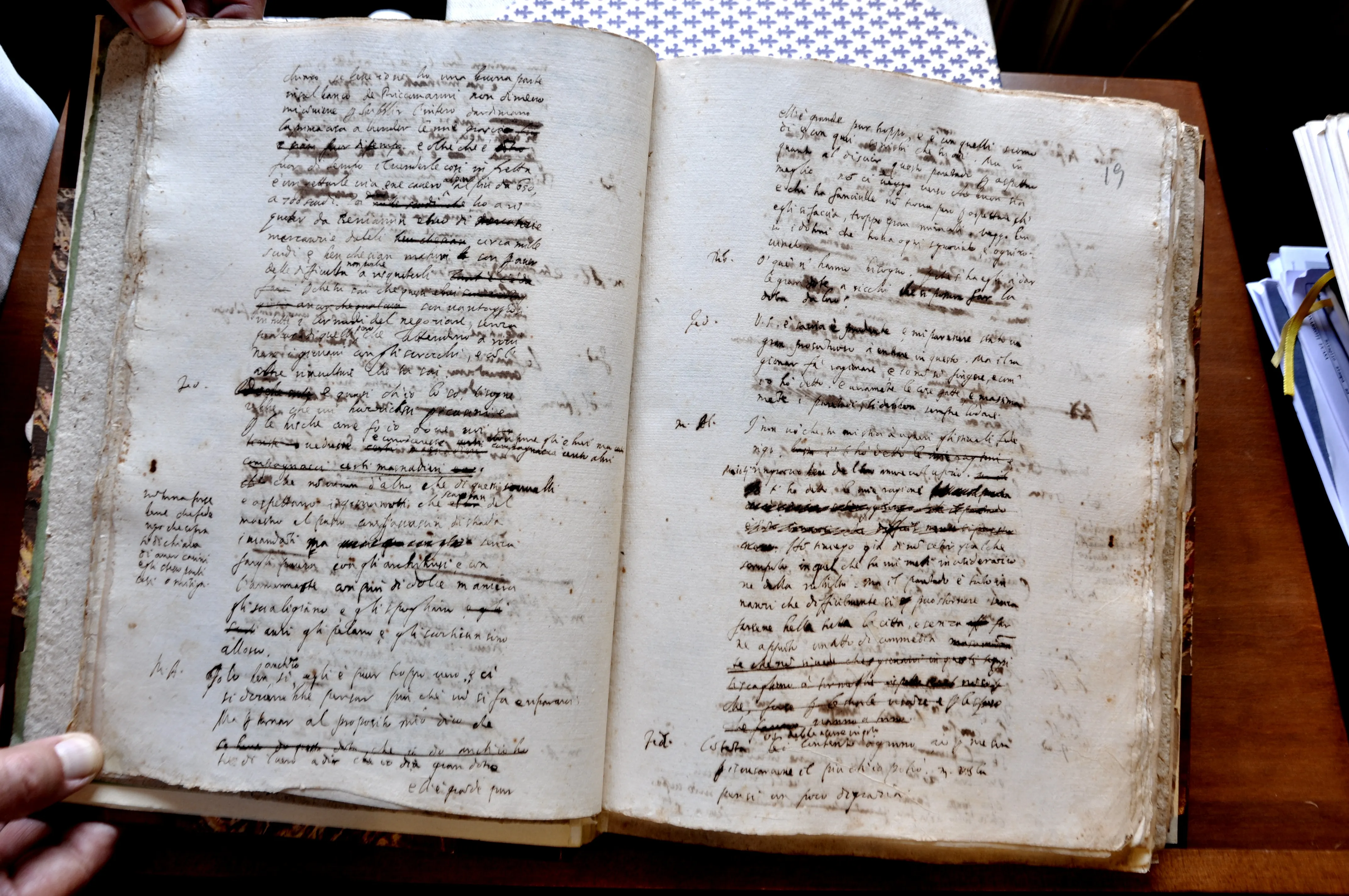

Far from finished, he left only the roughest of drafts—two hundred pages of scratch-outs and rewrites, marginal jottings and notes-to-self—often lively and sometimes brilliant, but nothing that he could bring to the stage any time soon. Meanwhile, the next Carnival at the Medici Court was rapidly approaching, scheduled for January 6 through February 11, 1614.

Why did Buonarroti set out to write a madcap Jewish comedy—in Florence, at that specific moment? Why was The Jew never published nor performed?

I work my way through a dizzying proliferation of people, places and events, all converging—then and there—on Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger.

●Sources

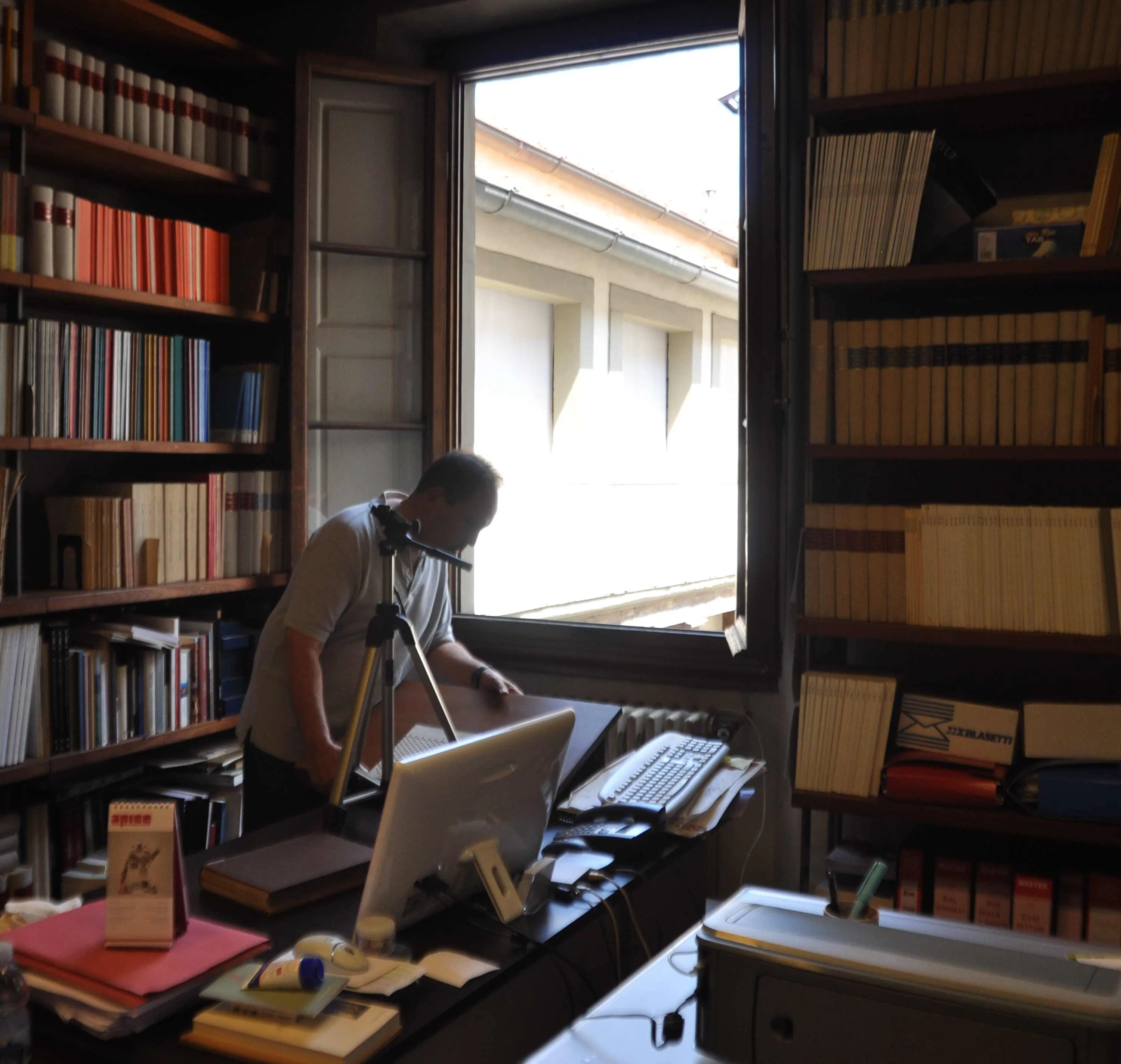

In this book, I rely on a wide range of primary and secondary sources, including archival documentation, scholarly studies (of uneven value) and my own experience (including site visits and on-the-spot interviews).

For me, the greatest challenge—as well as the greatest opportunity—was venturing into a largely unexplored area of history, making my own way as best I could. I soon discovered that most previous studies were scant at best, apart from a few notable exceptions that I gratefully cite.

Since I couldn’t construct a traditional bibliography or footnotes, without recycling material in which I had limited faith, I decided to offer an extensive running discussion at the back of the book. I retrace my footsteps, chapter by chapter, offering all the specific references I can—making it as easy as possible for others to continue the journey where I left off.